Dead Man’s Pass

Doug Braudaway

Southwest Texas Junior College, Del Rio, Texas 78840

(830) 703-1554; dbraudaway@swtjc.edu

During the frontier days of Texas, the roads through Southwest Texas in what is now Val Verde County were considered dangerous, even for the soldiers, on account of Indians. Soldiers and civilians made regular trips between San Antonio and El Paso were often attacked on their mail runs. Another place along the road north of modern Comstock was called “Dead Man's Pass” or “Dead Man's Run” where “many unfortunate travelers have lost their lives near the south entrance.”1 The place was described as a narrow canyon not far from Pecan Springs (on the Devil's River), and the graves of many men were dug along the road connecting San Antonio with El Paso.2

Zenas Bliss, a soldier who spent many years in Texas reminisced at length about his time in Southwest Texas. “The El Paso Road today from San Antonio to California would appear like one long grave if the innumerable graves had not been levelled by the elements. I do not believe that there is a single water hole or camping ground from one end of the road to the other that has not been marked with from one to fifty graves erected by soldiers or friends over the bodies of murdered travellers.”3

According to Texas legend Bigfoot Wallace, the "hardest fight" he had ever had against Indians took place in the Devil's River canyon where the bluffs were high and the road rough. The westbound stage had stopped for noon lunch when Comanches attacked Wallace and his party of six. The Comanches used arrows and bullets. The stage party successfully defended itself but retreated to Fort Clark because Wallace figured that they would be attacked again without a soldier escort. When no troops were provided, he backtracked further to Fort Inge—and received the same response. He sent a nasty letter to the San Antonio office saying that he was hiring three extra men from the Leona Station; he wrote that “if we cannot clear the road we shall fight it out with them.” The larger, newly-reinforced group made it through.4

The earliest dated fight and or killings in the Pass took place in 1849 (which is about as early as Americans were traveling through this countryside). The reference is vague, saying that “Two men with Dr. Lyon’s wagons at Deadman’s Pass” were killed.5 This may be the fight described in an 1898 newspaper account about an Indian fight taking place between 1849 and 1853. The biographical article describes a wagon train in the hire of Dr. Lyons coming back from El Paso, “arriving at ‘Dead Man’s pass’ with five wagons and thirteen men.” The wagon train was caught in an “ambuscade,” and when the fight was over, “The dead men were buried on the spot where the battle was fought.” This account tallies four of the teamsters killed and an unknown number of Indians.6

Jesse Sumpter recalled, from about 1850, a story of wagon trains along the Devil’s River. “When we reached Beaver Lake a lot of teamsters’ rations were running low, so they determined to make long drives to get into San Antonio for provisions. They got to what is now known as Dead Man’s Run, which is between California Springs and the second crossing of the Devil’s River. There the Indians attacked them while they were strung out on the road, and killed four, and wounded two or three.”7

The Fort Hudson army post was established to create a safe zone, however small, for travelers along the San Antonio-El Paso Road, though the small size of the garrison limited its effectiveness. After the establishment of the Devil’s River post—Wallace and his men were again ambushed, about fifteen miles of the post. After cutting the reins Wallace yelled to rest of the men “to ride for their lives.” The Comanche attackers looted the coach, but Wallace and the rest escaped to the post.9 That same party had earlier ambushed a Second Cavalry patrol north of the ambush site. The troopers, commanded by Lt. John Bell Hood, took and gave heavy casualties, so "the Comanches were understandably hungry for revenge when they attack the expressmen."10

Dead Man's Pass, nearby Beaver Lake and the Devil' s River country generally remained dangerous to those carrying freight. August Santleben recorded several deaths at the hands of Indians at each of these locations; nevertheless, he noted that bandits (of the American variety) and wild animals were also a threat.11 Still, in a list of Americans killed by Indians in western Texas, Santleben included “Mr. and Mrs. Amlung, their 3 children and 7 men at Deadman’s Pass” in 1858.12

Santleben himself had several close-calls in and near the Pass. “The next morning [sometime in 1873] we crossed the Devil’s River and nooned at Painted Cave. The following day General McKenzie overtook us at California Springs, where we had stopped for dinner, and he camped there. His command consisted of a regiment of cavalry and one company of [Black] Seminole [Scout] Indians, which accompanied by ten wagons and a hospital ambulance in charge of a surgeon. The general advised me to remain and travel under the protection of his troops to Beaver Lake, at the head of the Devil’s River…. I thanked him for his kind intentions… but told him it would be impossible for me to travel with his troops. So we left him there and camped that night at Dead-man’s Pass. We nooned the next day at Fort Hudson, that was abandoned in 1860 and was then unoccupied.”13

“Our return trip was devoid of interest until we passed Fort Hudson, when making a night drive, near, Dead-man’s Pass, considerable excitement was caused in that desolate region, about three o’clock in the morning, by an alarm that led us to believe that Indians were in our vicinity….” Livestock were stampeded, and lives were very nearly lost before control of the herd was reestablished. “The men insisted that the trouble was caused by Indians, but probably was a false alarm, and the mules may have been scared by a panther, bear, or Mexican lion….”14

Army Lt. Zenas Bliss recorded long detailed accounts of the Devil’s River countryside during his 1850s postings to Fort Hudson, and he mentioned the Pass. “Just before sun-set they [including a man named Dunlop] hitched up to make their evening drive, and had proceeded to near ‘Dead Man’s Pass’ about 12 miles from the Post. The train was strung out and traveling in the usual manner…[when] they received a volley from the Indians who were concealed in the ravine, and were near enough to almost touch the animals with their rifles.”15 The Indians severely injured some of the trail drivers and ran off much of the livestock. “The place where Dunlop was attacked, and wounded, was near Dead Man’s Pass, and but a short distance from California Springs, two well known places on the road. The former was so named because of the finding of a dead man there, by some parties traveling the road; and the latter on account of the massacre of a party on their way to California.16

During the American Civil War, little traffic passed though the Pass after the survivors of Sibley’s invasion of New Mexico returned to San Antonio in 1862. Fort Hudson disappeared during the War, but was reopened afterward as traffic again traveled the San Antonio-El Paso Road. Hudson was closed in 1877 as the Indian Wars in Texas were ending.

Like most landmarks in Val Verde County, Dead Man’s Pass is gone, paved over, and forgotten in the hum of modern life. Travelers on State Highway 163 are more likely to get hit by a tractor-trailer rig on the twisting roadway than attacked by Indians. But for some three decades, this spot in the future Val Verde County was one of the most dangerous and feared locations, enough so that a military post was established to keep the peace.

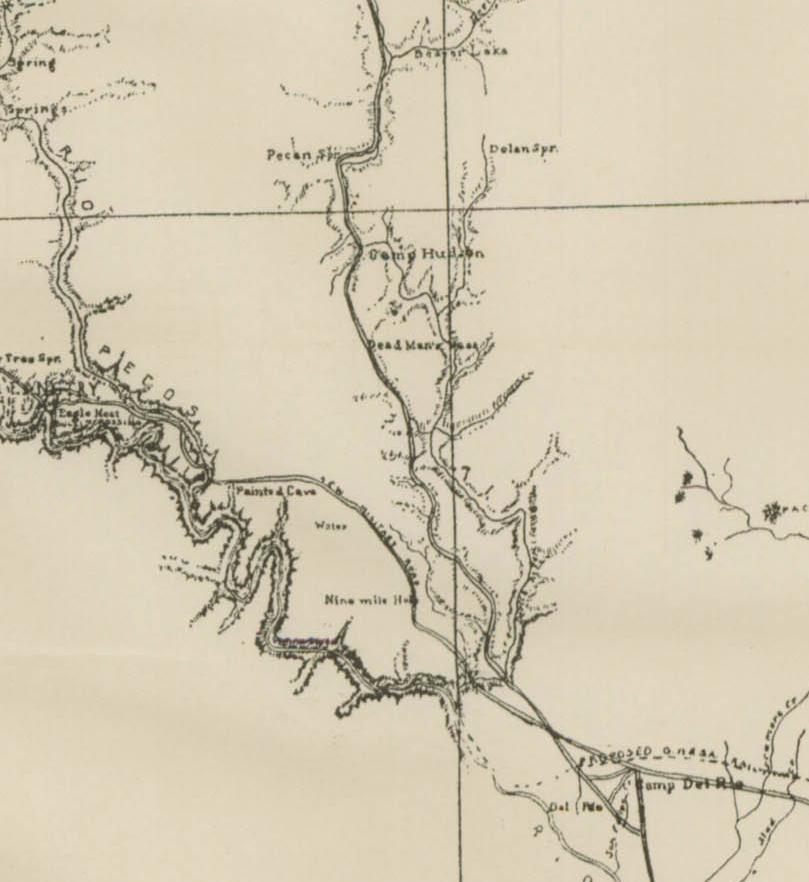

Appendix 1: General B.H. Grierson’s map of Western Texas.

Doug Braudaway

Southwest Texas Junior College, Del Rio, Texas 78840

(830) 703-1554; dbraudaway@swtjc.edu

During the frontier days of Texas, the roads through Southwest Texas in what is now Val Verde County were considered dangerous, even for the soldiers, on account of Indians. Soldiers and civilians made regular trips between San Antonio and El Paso were often attacked on their mail runs. Another place along the road north of modern Comstock was called “Dead Man's Pass” or “Dead Man's Run” where “many unfortunate travelers have lost their lives near the south entrance.”1 The place was described as a narrow canyon not far from Pecan Springs (on the Devil's River), and the graves of many men were dug along the road connecting San Antonio with El Paso.2

Zenas Bliss, a soldier who spent many years in Texas reminisced at length about his time in Southwest Texas. “The El Paso Road today from San Antonio to California would appear like one long grave if the innumerable graves had not been levelled by the elements. I do not believe that there is a single water hole or camping ground from one end of the road to the other that has not been marked with from one to fifty graves erected by soldiers or friends over the bodies of murdered travellers.”3

According to Texas legend Bigfoot Wallace, the "hardest fight" he had ever had against Indians took place in the Devil's River canyon where the bluffs were high and the road rough. The westbound stage had stopped for noon lunch when Comanches attacked Wallace and his party of six. The Comanches used arrows and bullets. The stage party successfully defended itself but retreated to Fort Clark because Wallace figured that they would be attacked again without a soldier escort. When no troops were provided, he backtracked further to Fort Inge—and received the same response. He sent a nasty letter to the San Antonio office saying that he was hiring three extra men from the Leona Station; he wrote that “if we cannot clear the road we shall fight it out with them.” The larger, newly-reinforced group made it through.4

The earliest dated fight and or killings in the Pass took place in 1849 (which is about as early as Americans were traveling through this countryside). The reference is vague, saying that “Two men with Dr. Lyon’s wagons at Deadman’s Pass” were killed.5 This may be the fight described in an 1898 newspaper account about an Indian fight taking place between 1849 and 1853. The biographical article describes a wagon train in the hire of Dr. Lyons coming back from El Paso, “arriving at ‘Dead Man’s pass’ with five wagons and thirteen men.” The wagon train was caught in an “ambuscade,” and when the fight was over, “The dead men were buried on the spot where the battle was fought.” This account tallies four of the teamsters killed and an unknown number of Indians.6

Jesse Sumpter recalled, from about 1850, a story of wagon trains along the Devil’s River. “When we reached Beaver Lake a lot of teamsters’ rations were running low, so they determined to make long drives to get into San Antonio for provisions. They got to what is now known as Dead Man’s Run, which is between California Springs and the second crossing of the Devil’s River. There the Indians attacked them while they were strung out on the road, and killed four, and wounded two or three.”7

The Fort Hudson army post was established to create a safe zone, however small, for travelers along the San Antonio-El Paso Road, though the small size of the garrison limited its effectiveness. After the establishment of the Devil’s River post—Wallace and his men were again ambushed, about fifteen miles of the post. After cutting the reins Wallace yelled to rest of the men “to ride for their lives.” The Comanche attackers looted the coach, but Wallace and the rest escaped to the post.9 That same party had earlier ambushed a Second Cavalry patrol north of the ambush site. The troopers, commanded by Lt. John Bell Hood, took and gave heavy casualties, so "the Comanches were understandably hungry for revenge when they attack the expressmen."10

Dead Man's Pass, nearby Beaver Lake and the Devil' s River country generally remained dangerous to those carrying freight. August Santleben recorded several deaths at the hands of Indians at each of these locations; nevertheless, he noted that bandits (of the American variety) and wild animals were also a threat.11 Still, in a list of Americans killed by Indians in western Texas, Santleben included “Mr. and Mrs. Amlung, their 3 children and 7 men at Deadman’s Pass” in 1858.12

Santleben himself had several close-calls in and near the Pass. “The next morning [sometime in 1873] we crossed the Devil’s River and nooned at Painted Cave. The following day General McKenzie overtook us at California Springs, where we had stopped for dinner, and he camped there. His command consisted of a regiment of cavalry and one company of [Black] Seminole [Scout] Indians, which accompanied by ten wagons and a hospital ambulance in charge of a surgeon. The general advised me to remain and travel under the protection of his troops to Beaver Lake, at the head of the Devil’s River…. I thanked him for his kind intentions… but told him it would be impossible for me to travel with his troops. So we left him there and camped that night at Dead-man’s Pass. We nooned the next day at Fort Hudson, that was abandoned in 1860 and was then unoccupied.”13

“Our return trip was devoid of interest until we passed Fort Hudson, when making a night drive, near, Dead-man’s Pass, considerable excitement was caused in that desolate region, about three o’clock in the morning, by an alarm that led us to believe that Indians were in our vicinity….” Livestock were stampeded, and lives were very nearly lost before control of the herd was reestablished. “The men insisted that the trouble was caused by Indians, but probably was a false alarm, and the mules may have been scared by a panther, bear, or Mexican lion….”14

Army Lt. Zenas Bliss recorded long detailed accounts of the Devil’s River countryside during his 1850s postings to Fort Hudson, and he mentioned the Pass. “Just before sun-set they [including a man named Dunlop] hitched up to make their evening drive, and had proceeded to near ‘Dead Man’s Pass’ about 12 miles from the Post. The train was strung out and traveling in the usual manner…[when] they received a volley from the Indians who were concealed in the ravine, and were near enough to almost touch the animals with their rifles.”15 The Indians severely injured some of the trail drivers and ran off much of the livestock. “The place where Dunlop was attacked, and wounded, was near Dead Man’s Pass, and but a short distance from California Springs, two well known places on the road. The former was so named because of the finding of a dead man there, by some parties traveling the road; and the latter on account of the massacre of a party on their way to California.16

During the American Civil War, little traffic passed though the Pass after the survivors of Sibley’s invasion of New Mexico returned to San Antonio in 1862. Fort Hudson disappeared during the War, but was reopened afterward as traffic again traveled the San Antonio-El Paso Road. Hudson was closed in 1877 as the Indian Wars in Texas were ending.

Like most landmarks in Val Verde County, Dead Man’s Pass is gone, paved over, and forgotten in the hum of modern life. Travelers on State Highway 163 are more likely to get hit by a tractor-trailer rig on the twisting roadway than attacked by Indians. But for some three decades, this spot in the future Val Verde County was one of the most dangerous and feared locations, enough so that a military post was established to keep the peace.

Appendix 1: General B.H. Grierson’s map of Western Texas.

Dead Man’s Pass appears on this 1883 map of Western Texas. This segment shows the future Val Verde County (organized in 1885).17

General Benjamin Henry Grierson served in the Army during the Civil War. After the war, he organized the Tenth United States Cavalry, one of the regiments of Buffalo Soldiers, and served in Indian Territory and Texas. In 1880 he and his men defeated Victorio effectively ending the Indian Wars in West Texas. During 1883 Grierson commanded the Department of Texas (and his picture appears with his entry in the New Handbook of Texas).

Appendix 2: the New Handbook of Texas includes a reference to the Pass.

DEAD MANS CREEK (Val Verde County). Dead Mans Creek rises 1½ miles southwest of Dead Mans Pass in south central Val Verde County (at 29°46' N, 101°10' W) and runs southeast for thirteen miles to its mouth on the Devils River, a mile south of Dark Canyon (at 29°44' N, 101°01' W). Its course sharply dissects massive limestone that underlies flat terrain, forming a deep and winding canyon. Soils in the area are generally dark, calcareous stony clays and clay loams that support oak, juniper, grasses, and mesquite. The creek was named for a traveling peddler who was robbed and killed by outlaws in a pass on the stream in the 1880s. Reportedly the outlaws openly sold the stolen cloth and kitchenware to workers building the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railway, and Judge Roy Bean refused to hear the case because the robbery occurred east of the Pecos River and out of his jurisdiction.

Bibliography--

Wayne R. Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules: The SanAntonio-El Paso Mail, 1851-1881, College Station: Texas A&M; University Press, 1985.

Jim Baker, “Notes,” undated typescript in “Baker’s Crossing” file at Val Verde County Library. The Baker Family has ranched in the area for a century and several members have collected stories from the area.

Zenas Bliss Papers. Five Volumes of Typescript, Center for American History, University of Texas (Austin).

New Handbook of Texas. “Dead Mans Creek” and “Benjamin Henry Grierson.”

Ben E. Pingenot (ed.), Paso Del Águila: A Chronicle of Frontier Days on the Texas Border as recorded in the Memoirs of Jesse Sumpter, The Encino Press, 1969.

August Santleben, (I.D. Affleck, ed.), A Texas Pioneer: Early Staging and Overland Freighting Days on the Frontiers of Texas and Mexico, The Neale Publishing Company: New York, 1910.

A.J. Sowell, “Texas Pioneers: John L. Mann,” Dallas Morning News, February 20, 1898, page 22.

A.J. Sowell, Life of “Bigfoot" Wallace: The Great Ranger Captain, Austin: State House Press, 1989.

Endnotes-

1 Santleben, A Texas Pioneer, page 100.

2 Bliss Papers, Vol. II, pages 88-89, 99-100; Pingenot, Paso Del Aguila, page 7.

3 Bliss Papers, Vol. 1, page 241.

4 Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, pages 30-31; Sowell, Life of “Bigfoot" Wallace, pages 138-140.

5 Santleben, A Texas Pioneer, page 262.

6 Sowell, “Texas Pioneers: John L. Mann,” page 22.

7 Pingenot, Paso Del Águila, page 7. The second crossing of the Devil’s River is approximately where State Highway 163 crosses the Devil’s at Baker’s Crossing and short distance from the future Fort Hudson location.

8 Baker, Notes; Bliss, Vol. II, page 151. Santleben records other Indian attacks at the Eighteenth Crossing of the San Antonio-El Paso Road, which was north of the post near Beaver Lake. W. Houston was killed in 1859, and W. Hudson in 1862. In 1873, Thomas Black was killed near Beaver Lake. Santleben, A Texas Pioneer, pages 264, 265, and 268.

The contemporary records call the post “Camp Hudson”—probably because of its small size. I am using “Fort Hudson” because of a twentieth-century practice of naming non-combat posts, usually training camps, “Camp”. Camp Hudson was a combat post, better represented by the title “Fort”.

9 Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, page 95.

10 Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, page 96.

11 Santleben, A Texas Pioneer, pages 137-138, 153-155, 264-268.

12 Santleben, A Texas Pioneer, page 264.

13 Santleben, A Texas Pioneer, page 150.

14 Santleben, A Texas Pioneer, pages 154.

15 Bliss Papers, Vol. II, pages 155-156.

16 Bliss Papers, Vol. II, page 160.

17 The whole map (which is quite large) may be found at the Texas State Library or at . 18 Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. "Dead Mans Creek,"

DEAD MANS CREEK (Val Verde County). Dead Mans Creek rises 1½ miles southwest of Dead Mans Pass in south central Val Verde County (at 29°46' N, 101°10' W) and runs southeast for thirteen miles to its mouth on the Devils River, a mile south of Dark Canyon (at 29°44' N, 101°01' W). Its course sharply dissects massive limestone that underlies flat terrain, forming a deep and winding canyon. Soils in the area are generally dark, calcareous stony clays and clay loams that support oak, juniper, grasses, and mesquite. The creek was named for a traveling peddler who was robbed and killed by outlaws in a pass on the stream in the 1880s. Reportedly the outlaws openly sold the stolen cloth and kitchenware to workers building the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railway, and Judge Roy Bean refused to hear the case because the robbery occurred east of the Pecos River and out of his jurisdiction.

Bibliography--

Wayne R. Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules: The SanAntonio-El Paso Mail, 1851-1881, College Station: Texas A&M; University Press, 1985.

Jim Baker, “Notes,” undated typescript in “Baker’s Crossing” file at Val Verde County Library. The Baker Family has ranched in the area for a century and several members have collected stories from the area.

Zenas Bliss Papers. Five Volumes of Typescript, Center for American History, University of Texas (Austin).

New Handbook of Texas. “Dead Mans Creek” and “Benjamin Henry Grierson.”

Ben E. Pingenot (ed.), Paso Del Águila: A Chronicle of Frontier Days on the Texas Border as recorded in the Memoirs of Jesse Sumpter, The Encino Press, 1969.

August Santleben, (I.D. Affleck, ed.), A Texas Pioneer: Early Staging and Overland Freighting Days on the Frontiers of Texas and Mexico, The Neale Publishing Company: New York, 1910.

A.J. Sowell, “Texas Pioneers: John L. Mann,” Dallas Morning News, February 20, 1898, page 22.

A.J. Sowell, Life of “Bigfoot" Wallace: The Great Ranger Captain, Austin: State House Press, 1989.

Endnotes-

1 Santleben, A Texas Pioneer, page 100.

2 Bliss Papers, Vol. II, pages 88-89, 99-100; Pingenot, Paso Del Aguila, page 7.

3 Bliss Papers, Vol. 1, page 241.

4 Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, pages 30-31; Sowell, Life of “Bigfoot" Wallace, pages 138-140.

5 Santleben, A Texas Pioneer, page 262.

6 Sowell, “Texas Pioneers: John L. Mann,” page 22.

7 Pingenot, Paso Del Águila, page 7. The second crossing of the Devil’s River is approximately where State Highway 163 crosses the Devil’s at Baker’s Crossing and short distance from the future Fort Hudson location.

8 Baker, Notes; Bliss, Vol. II, page 151. Santleben records other Indian attacks at the Eighteenth Crossing of the San Antonio-El Paso Road, which was north of the post near Beaver Lake. W. Houston was killed in 1859, and W. Hudson in 1862. In 1873, Thomas Black was killed near Beaver Lake. Santleben, A Texas Pioneer, pages 264, 265, and 268.

The contemporary records call the post “Camp Hudson”—probably because of its small size. I am using “Fort Hudson” because of a twentieth-century practice of naming non-combat posts, usually training camps, “Camp”. Camp Hudson was a combat post, better represented by the title “Fort”.

9 Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, page 95.

10 Austerman, Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, page 96.

11 Santleben, A Texas Pioneer, pages 137-138, 153-155, 264-268.

12 Santleben, A Texas Pioneer, page 264.

13 Santleben, A Texas Pioneer, page 150.

14 Santleben, A Texas Pioneer, pages 154.

15 Bliss Papers, Vol. II, pages 155-156.

16 Bliss Papers, Vol. II, page 160.

17 The whole map (which is quite large) may be found at the Texas State Library or at . 18 Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. "Dead Mans Creek,"